Reading through all the positive press about jobs numbers and so forth, its hard to comprehend that the 4 main indicators used by the National Buro of Economic Research (NBER) to determine US recessions, had a narrow miss recently.

If you recall from our popular 2012 article, the NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. Rather, a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.

With regards to the monthly data, they examine 4 monthly co-incident indicators:

- Industrial Production

- Real personal income less transfers deflated by personal consumption expenditure

- Non-farm payrolls

- Real retail sales deflated by consumer price index

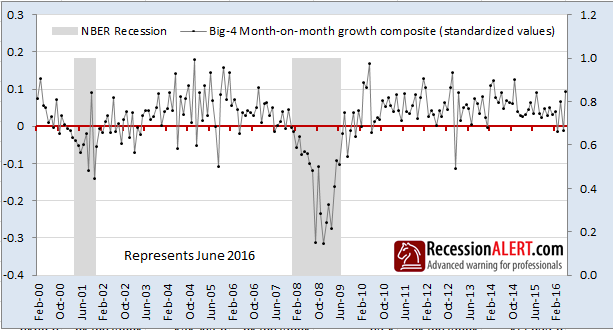

If one takes the month-on-month percentage change of these four data series, and combine them into a standardized average composite, you get the below, where we had negative prints for February and May:

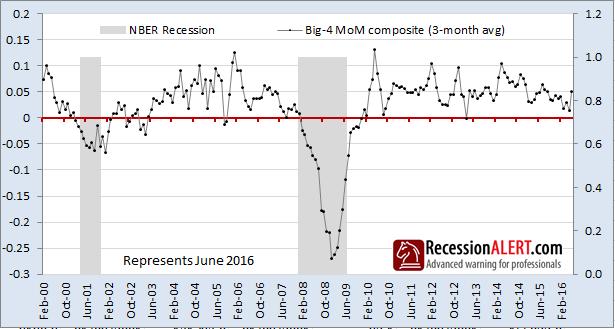

Taking a moving average of the above to smooth out volatility, we get the following index that reliably signals recession when it turns negative. Lets call this event Syndrome-One

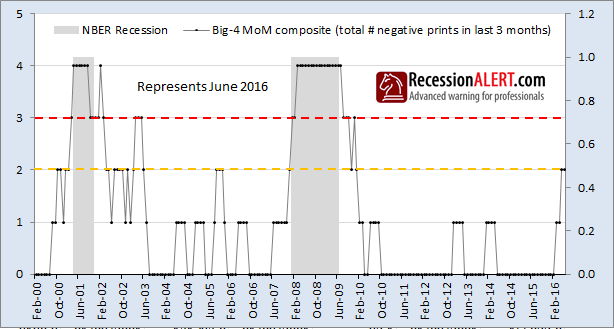

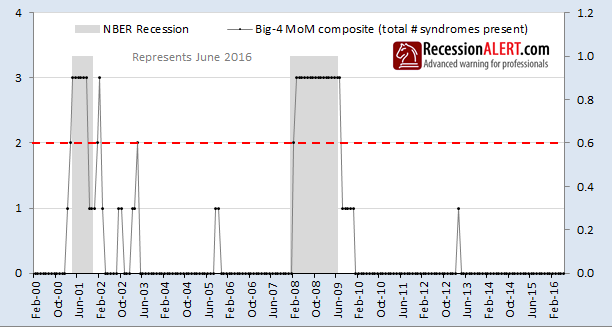

We can also count the amount of times the non-smoothed month-on-month indicator in the first chart has dipped below zero in a rolling 4-month period. When this count reaches 2 we are in a “danger zone” and when it hits 3, we are most likely already in a recession. We hit the danger zone in May and June. Lets call this count reaching three Syndrome-Two.

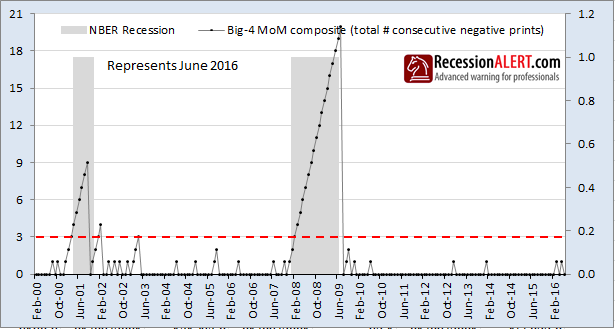

Another interesting thing to note is how many consecutive negative prints the indicator in the first chart has made. When this hits three we are also most likely in a Recession. Lets call this event Syndrome-Three:

The below Syndrome count shows how many of the three syndromes are present at any time. If two or more syndromes are present, we are most likely already in recession.

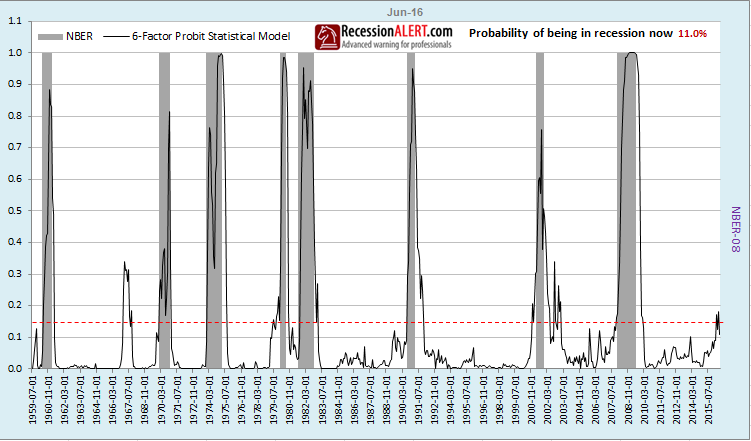

We run a more sophisticated algorithm for the Big-4 for our subscribers, as described in this robust tested methodology, and here are the probabilities of recession from the model:

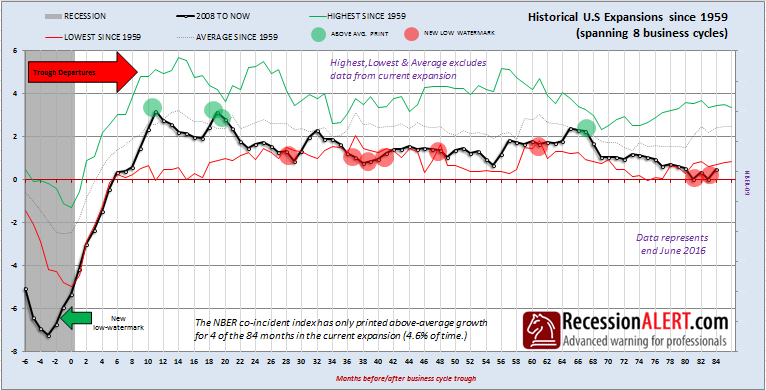

To conclude, looking at the individual co-incident monthly data used by the NBER shows a far more pessimistic view currently than when looking at a syndrome of conditions. But the co-incident data in this particular indicator and the recession probabilities we are registering are not as bullish as the employment data would have you think. In fact, taking our proprietary implementation of the Big-4 index, and comparing it to the last 8 expansions, shows just how meek this recovery has been:

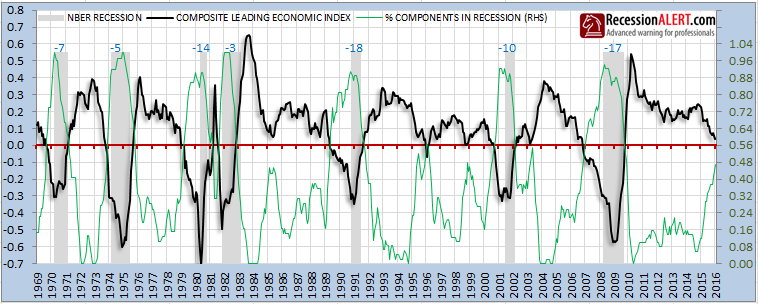

There is one final interesting observation though – for the first time this expansion, the co-incident data is coinciding with the weak leading economic data made from 21 leading data series and first witnessed for February 2016. And that’s something worth pondering about.

Comments are closed.